Risks of Global Manufacturing Value Chain Transformation

By Industry Analyst Su Han-Yang

What Drives the Fragmentation of Global Value Chains?

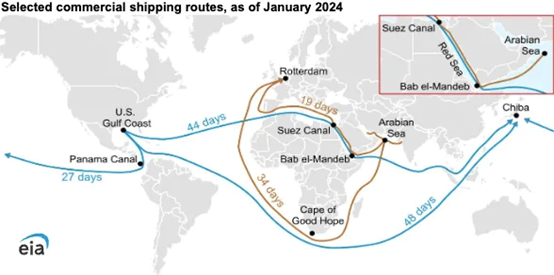

As geopolitical events and trends exert pressure on governments and corporate decision-makers, the value of global supply chains and strategically important emerging technologies are being reassessed. Meanwhile, China’s rise, climate change, advanced technologies, and recent intensified conflicts such as the Russia-Ukraine war and Middle East tensions are prompting a reevaluation of supply chain vulnerabilities and the value of globally distributed networks. Resilient supply chains—those designed to withstand geopolitical uncertainty rather than being driven solely by cost considerations—are sweeping across industries.

Historically, the end of the Cold War marked the triumph of democracy and ushered in an era of globalization. This globalization was enabled by commitments to shared international governance structures and comprehensive trade liberalization led by policymakers in the U.S., Europe, East Asia, Latin America, and beyond. The so-called “Washington Consensus” became synonymous with this era, where economic efficiency and specialization were paramount, and supply chains crossed geopolitical fault lines to seek lower wages and input costs worldwide.

|

Source: Resilinc (2024)

Natural Disasters and Early Warning Signs

The 2011 Fukushima earthquake was the first major event to expose vulnerabilities in semiconductor supply chains. That same year, severe flooding in Thailand reinforced lessons learned from Fukushima: downstream manufacturers relying heavily on a few suppliers in disaster-prone countries (Japan and Thailand) faced critical risks. Other natural disasters—such as Hurricane Sandy in the U.S. (2012) and famines in parts of Africa—also disrupted supply chains. Global firms now rank natural disasters and extreme weather as top risks to uninterrupted operations, alongside political unrest and social conflicts like the Arab Spring. Before COVID-19 emerged in January 2020, unexpected IT outages, cyberattacks, data breaches, and severe weather were already considered major causes of supply chain disruptions.

Reshoring and “Like-Minded” Alliances

Efforts to relocate production from mainland China to “like-minded” countries hinge on financial incentives. Japan, Australia, and India have announced policies:

- Japan offers subsidies to encourage firms to move operations out of China.

- India introduced production-linked incentives to boost local capacity across sectors.

- Australia launched an economic plan to strengthen supply chain resilience and domestic manufacturing.

Despite these measures, results will take time to materialize.

The U.S. Strategy: Decoupling from China

The U.S. leads the charge in reducing reliance on China. Its strategy includes building trusted networks among allies and partners. Initiatives like the U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council (TTC) signal transatlantic interest in supply chain coordination and trust-building. A joint statement from the May 2022 TTC meeting pledged to “reduce dependence on unreliable strategic suppliers” and “mitigate sudden supply chain disruptions,” while lowering trade barriers.

Another focus is reducing single-point failure risks, such as Asia’s dominance in semiconductor manufacturing. The U.S. and Europe aim to lessen dependence on Taiwan and South Korea, which together account for about half of global semiconductor capacity. Diplomatic efforts—such as the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, the Quad (U.S., Australia, Japan, India), and the U.S.-Taiwan 21st Century Trade Initiative—are complemented by direct investments in Vietnam, India, and Australia to diversify risk.

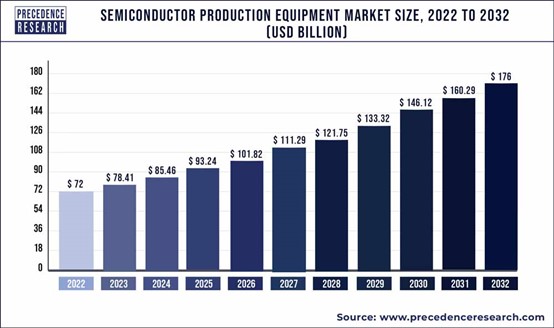

Semiconductors: A Strategic Reconfiguration

The U.S.-led restructuring of global value chains began with semiconductors. To address chip shortages, U.S. lawmakers are pushing to build domestic manufacturing capacity and reduce reliance on Taiwan. Despite skepticism—TSMC’s former chairman called U.S. efforts “costly and futile”—policymakers insist diversification is critical. The CHIPS Act allocates $52 billion to restore advanced chip manufacturing in the U.S., including $39 billion for fabrication plants and $12 billion in subsidies.

|

Source: Precedence Research (2024)

Europe followed suit, mobilizing €43 billion in public and private funds to double its share of global semiconductor production by 2030. EU leaders stress open markets and partnerships with “like-minded” nations such as the U.S. and Japan to balance interdependence and reliability.

|

Source: Compiled by the author (2024)

Recent CHIPS Act Grants (Highlights)

- Dec 2023: $35M to BAE Systems for defense-related equipment.

- Jan 2024: $162M to Microchip Technology for microcontroller capacity.

- Feb 2024: $1.5B loan to GlobalFoundries for U.S. plant expansion.

- Mar 2024: Up to $11B to Intel for facilities in Ohio, Arizona, New Mexico, Oregon.

- Apr 2024: $6.14B to Micron for memory fabs; $6.6B grant + $5B loan to TSMC for Arizona plants.

- May 2024: $120M to Polar Semiconductor; $75M to Absolics for glass substrate factory.

- Aug 2024: $450M to SK Hynix for advanced memory chip center.

China’s Position and Challenges

Since 2019, the U.S. has imposed sanctions on Chinese tech firms, escalating in 2022 with bans on semiconductor exports—joined by Japan and the Netherlands. China imports more semiconductors than oil, with 86% of chipmaking equipment sourced abroad as of 2022. Sanctions caused China’s equipment purchases to fall for the first time in a decade. While Washington seeks to freeze Beijing’s tech capabilities rather than halt all production, China is expected to intensify R&D efforts. The question remains whether Western nations can match investments to maintain their technological edge.

Legacy chips—essential for cars, computers, and appliances—were the main bottleneck during COVID-era shortages, not cutting-edge chips. China remains a major player in legacy chip production and consumption, with 30% of global semiconductor sales going to China. Many chips pass through China during development, giving it leverage over global supply chains. As firms seek to diversify away from China, packaging operations are gradually relocating, driven by U.S. policies balancing economic integration with national security concerns.

The Second Battleground: Electric Vehicles (EVs)

In 2023, China, the U.S., and Europe accounted for over 65% of global auto sales and 95% of EV sales—China alone held 60%. China dominates EV battery production (83% of global output) and nearly 60% of EV manufacturing. While mining of critical minerals is geographically dispersed, China controls most processing:

- Lithium: >65%

- Nickel: >35%

- Cobalt: >75%

- High-purity manganese: >90%

- Graphite: ~100%

By 2030, 70% of global battery capacity is projected to be in China, which also controls half of global battery recycling.

China’s EV industry has thrived on government support since 2009, including subsidies, tax exemptions, and infrastructure incentives. Between 2009 and 2022, China spent over $28 billion on EV subsidies and tax breaks.

BYD: A Case Study in Vertical Integration

BYD exemplifies China’s strategy, controlling the entire supply chain—from mining and batteries to vehicle manufacturing and logistics—enabling competitive pricing and rapid expansion. It is among the world’s largest lithium battery producers, even supplying competitors like Tesla. BYD’s self-sufficiency in batteries and semiconductors, plus in-house production of nearly all auto components, gives it a cost advantage over rivals.

National Security and Strategic Industries

The concept of national security varies but often favors domestic production. In the 1960s–70s, U.S. oil producers argued imports threatened security, while oil majors claimed cheap imports enhanced it. Similarly, EV imports may accelerate decarbonization and climate resilience, while domestic EV manufacturing preserves jobs and security. Beyond semiconductors and EVs, future value chain realignments merit close observation.